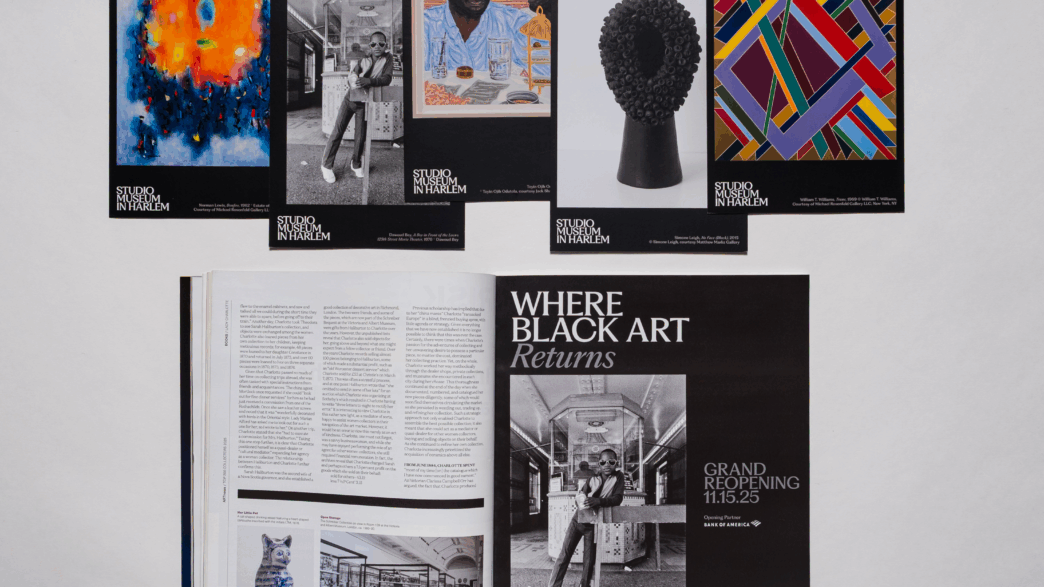

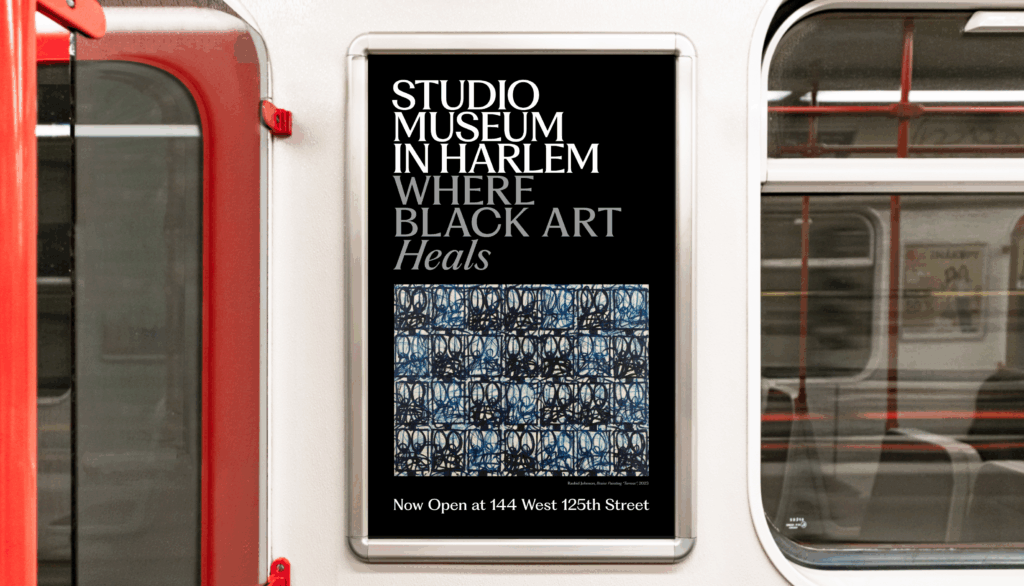

This weekend, the Studio Museum reopens its doors in a gleaming new building—ushering in a fresh chapter for New York’s premier institution dedicated to Black art. After more than seven years of construction, the museum emerges transformed, yet deeply rooted in its original mission. The streets around it are now dotted with vibrant signs and permanent installations, celebrating Harlem’s role as a cultural engine for Black imagination for over a century.

Inside, the museum feels both new and familiar. Expanded studios for its iconic artist-in-residence program signal a renewed commitment to nurturing emerging talent, while newly commissioned works mark the institution’s long-awaited reboot. But the Studio Museum is also turning back the clock with a retrospective of Tom Lloyd, whose electronically programmed sculptures foreshadowed today’s digital art landscape. Some of Lloyd’s pieces were part of the museum’s first-ever exhibition in 1968—a time when mainstream New York museums rarely showed work by Black artists.

Today, the landscape is radically different. Artists like Rashid Johnson and Amy Sherald routinely headline shows at institutions such as the Guggenheim and the Whitney. Studio Museum director Thelma Golden, who spearheaded the $300 million rebuild, reflects on this shift with pride. The change, she notes, is inseparable from the museum’s influence—its early insistence that Black art belonged not at the margins but at the center of cultural conversation. Yet, as Golden reminds visitors, “the work continues to need to be done.”

The museum’s history is lovingly preserved throughout its halls—photos from the 1968 groundbreaking, posters for jazz nights and “Uptown Fridays,” and archives of groundbreaking exhibitions. From the start, founders envisioned a space unlike any of New York’s traditional institutions. They wanted a home for “truly current work”—art that might be fleeting or revolutionary. They also dreamed of redefining Harlem itself, countering stereotypes while building community across racial and social divides.

Today, that vision radiates from the museum’s striking new façade. A red, black, and green flag by David Hammons waves proudly—a nod to Pan-African heritage. Houston Conwill’s “The Joyful Mysteries,” a monument to Black voices and legacy, hides time capsules meant for 2034. And the building itself—bold, geometric, unapologetically Harlem—marks a milestone in the museum’s journey. As the doors open once again, the Studio Museum stands as both a tribute to its predecessors and a beacon for future generations, redefining what a museum can be, and who it’s for.